Coding for the Courtroom

Top law schools aim to prepare lawyers for an AI-driven legal world

Artificial intelligence is no longer science fiction. It is changing how law is practiced, how contracts are read, how privacy is enforced, and how justice is imagined. Yale, Harvard, and Stanford Law Schools are rewriting legal education. Code, agents, and technical fluency are no longer optional. They are survival skills in a world where an agent based on an algorithm can already draft your brief or analyze your lawsuit.

While notable names in tech like Dr. Alex Karp (JD) of Palantir have argued that the traditional model of higher education is becoming less aligned with what the world needs, top law schools are trying to keep up as the legal world faces a massive shift.

At Yale, the focus is hands-on experimentation and interdisciplinary learning. The Yale AI Lab brings students and faculty together to build tools that address real legal challenges, like a defamation detector created with the Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic. Courses like Law and Large Language Models and Technology in the Practice of Law teach students to critique and build the technologies shaping their field.

Harvard emphasizes technical literacy. CS50 for Lawyers teaches programming, algorithms, and systems thinking so graduates can understand the systems they will advise on or litigate against. Lawyers working on privacy, intellectual property, or algorithmic bias must understand how code works to survive. Those who cannot read or reason about a system risk being left behind.

Stanford Law is pushing further. Its Legal Innovation through Frontier Technology Lab prototypes tools like contract-risk models and AI-driven legal aid systems. Courses such as Lawyering for Innovation: Artificial Intelligence and Governing Artificial Intelligence explore technical mechanics and regulatory challenges. AI for Legal Help partners students with legal aid groups to design AI tools that expand access to justice.

Understanding code and agents is now fundamental. Large language model agents already handle research, drafting, and compliance work once done by junior associates. Lawyers who can interpret, audit, and guide these systems will define the next era of practice.

The practice of law is becoming inseparable from computation. Coding is to the modern lawyer what Latin was to the jurist of the Renaissance. By learning AI, students gain the tools to question the logic behind contracts, compliance, and justice itself.

In this context, it becomes conceivable that traditional degree requirements may one day become optional. If mastery of technical systems, AI literacy, and applied problem-solving increasingly define legal competence, the formal JD may be less necessary than the skills it once guaranteed. As Karp has suggested, the world no longer demands that higher education conform to outdated structures. For law, that could mean a future where practical fluency with agents, algorithms, and systems is more important than the credentials once deemed essential.

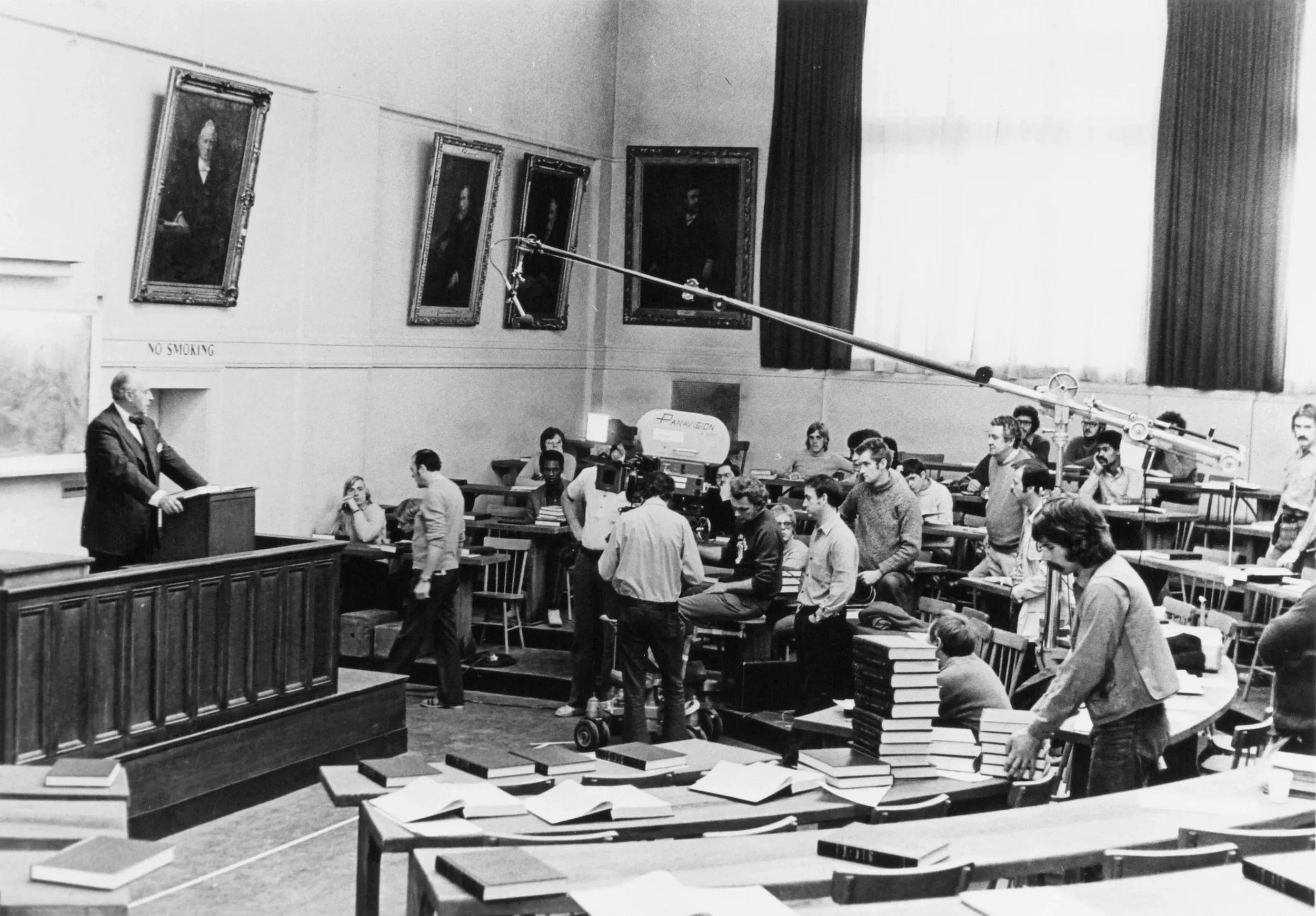

A still from the film “Paper Chase” shot at Harvard Law School